The curtains go up, the lights go down, and Anna (Nicole Kidman) thinks back over the last decade of her life. Her husband, a professor, has died while running in Central Park on a frigid winter’s day. His last lesson is about the possibility of reincarnation and the limits of belief. Anna has grieved, though perhaps she’s not moved on entirely, and now, after a reasonable amount of time, a modest amount of time, finds herself engaged to Joseph (Danny Huston). Joseph, who loves her, who means well, solid/stolid Joseph, who is adequate in every way, but after all, is not Sean. No one could be Sean. There was only one Sean.

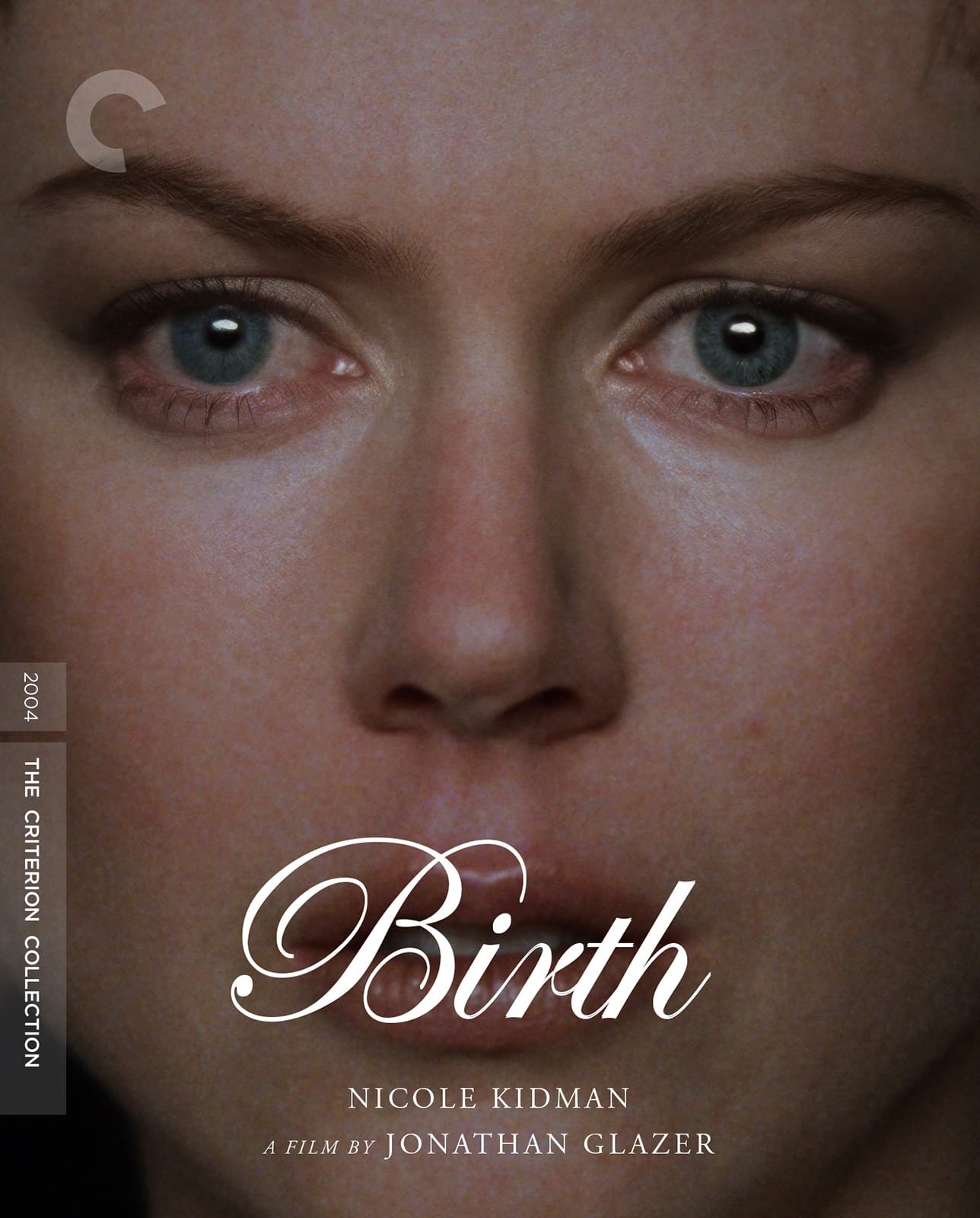

So here’s Anna on the horns of a dilemma. The curtains go up. The lights go down. In extreme close-up, now we’ll watch just her face for the next two minutes as she silently plays out her personal drama against the backdrop of impossible ideas drawing her in like deep water seduces a diver running out of air. It’s a performance worthy of Falconetti’s “Passion of Joan of Arc” (Dreyer, 1929). Old money Anna. Beautiful, fragile Anna. Ferocious, broken Anna, making peace with eternity before a ritualized event enacting a sacred score. The last 110 minutes of this film will be the price she must pay for touching the face of the sublime.

Anna is watching Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” twenty-seven minutes into Jonathan Glazer’s “Birth” (2004)—an epic opera that, at its heart, is about a love between two people that surpasses every attempt, mortal or supernatural, to tear them apart. That’s what “Birth” is about, too. Glazer seems to have an intimate understanding of the “Götterdämmerung” and its implications for mortals. A good argument can be made that the long opening of Glazer’s “Under the Skin” (2013) is set to the cadences of Wagner’s prologue, the steady rise from a primordial nothing to a series of climaxes that will eventually culminate in the twilight of the Gods. It is his muse, and he invokes it as the call to a great adventure on the back of an unsolvable mystery, the resolution of which is the end of reason, the end of the self.

Even with only four films in twenty-five years, Glazer is among our most important living filmmakers. He is a philosopher in absolute control of his instrument. His obsession is unpacking the nature of the human beast in all its manifold complexities, all its perverse, self-justifying peculiarities. His universe is immense and meaningless. Wisdom brings no profit to the wise, here. Anywhere. Never did. Glazer wishes to explain the ways of Man to men, and in this way, he is the most existentially empathetic transcendental filmmaker since Terrence Malick.

What’s happened to Anna is that Sean has returned to her in the body of a child, Sean (Cameron Bright), the son of a music tutor who works in Anna’s building. Sean sees Anna come and go, and one day he recognizes her as his wife and tells her so during her birthday party. When he first crashes her small, dark celebration, he’s unnoticed, even by Glazer, who fixes his camera on Anna, Anna’s mother (Lauren Bacall), and sister Laura (Alison Elliott), fussing about a cake in the dim light provided by its candles. His voice, a child’s voice, asking to speak with Anna alone, comes from off-screen. This is how Sean re-enters Anna’s life: a disembodied voice, an urgent request, a ghost. For the first quarter of the film, Sean tries to convince Anna that he’s her husband returned in this form.

My daughter met my uncle, the last surviving sibling of four, in Taiwan this year, and I told a cousin how glad I was that she would be able to see an echo of my father at last. My father, who died a month before she was born. My cousin laughed and said I was the exact reflection of my father. Maybe we’re all composed of pieces of the people who came before us. Maybe “Birth” forces us to see that. Anna goes to the opera and decides she’s going to believe Sean. These spaces where art is returned to ritual and religion, theaters and museums substituting for caves and forest clearings, are where impossible things are not impossible, and nothing ever dies, not really. If you’re able to believe in anything, these holy places are where you’re most likely to.

Although “Birth” is Glazer’s second film after his concussive crime drama “Sexy Beast,” it’s the first to be obviously identifiable as such. With cinematographer Harris Savides, he sought to emulate the umber closeness of Georges de La Tour’s paintings: a French master caught somewhere between Rembrandt and Edward Hopper, whose palette was nostalgia and melancholy, Proustian contemplation and a dangerous, isolating solipsism.

“Birth” is the first time I noted the work of the now seemingly-ubiquitous Parisian composer Alexandre Desplat as well. His score for “Birth” is a masterpiece of waltzes in a minor scale, suggesting an endless dance between Anna and Sean marred by small missteps and minor crises of faith. Every stumble is evidence of Anna’s disintegrating faith. Watch the final shots of the film as Anna stumbles in the surf of a frigid beach in her sodden wedding dress. It’s an image taken directly from Derek Jarman’s “The Last of England” (1987) and carries the same kind of profane, the same species of the mysterious occupying as this shot does a liminal space between the forever of the ocean and the multiplicity of the waterfront. It looks like Anna’s a marionette with a few broken strings. She looks like the seafoam the Little Mermaid turns into at the end of the Hans Christian Andersen story, when she fails to win her love for the loss of her voice, roiled and tossed by the capriciousness of the tide. Most of all, she looks like the last dancer at a lavish ball, spent and on the verge of collapse.

Sound designer Johnnie Burn, collaborating with Glazer here for the first time as well, fills in the aural spaces with low bass thrums, menacing and unidentifiably familiar, too. He makes what we can’t know an immense thing: a steep rock face with no purchase, and the tide is filling in behind us. With Desplat’s score, it tells the story of Anna’s grief, and in those last moments, it becomes all of our grief. Weren’t we promised absolution? Haven’t we earned a measure of peace? Where is it?

“Birth” was hounded upon its release with bad faith interpretations of it being somehow an apologia for pedophilia—that Anna was criminal for wanting to believe her husband had come back to her in the body of a child, the exact age of the length of time her husband had been dead. The fulcrum of the scandal is a scene in a shared bath where Sean and Anna talk, half-submerged. Water is a trope in “Birth.” Everything it means in literature, it means here, too: baptism, cleansing, rebirth. It seems only appropriate that the last twenty-some years have given “Birth” time to find a cult around its patience and the overwhelming richness of its Romanticist poetry. It’s a movie about what it means to love someone forever in a world that’s temporary. It’s about the unimaginable tragedy of every love story that must end with one partner predeceasing the other. It’s about what we do now when what can’t happen, happens. It happens all the time.

“Birth” is about the miracle of persistence and perseverance. Where do we find the strength to go on? How do we fight against the persistent undertow tugging at us with its promises of cold comfort in its black embrace? Kidman is extraordinary as Anna, matched by young Bright and poor, befuddled, humiliated, and emasculated Huston. The star of the show, though, might be the late, lamented Anne Heche, who plays Anna’s less-advantaged friend who opens the film by burying a box of letters in the park in the first of several literary gestures in a film that eventually reads like a Virginia Woolf novel. Heche’s Clara is, as typical of Heche, a bundle of nervous energy and barely-restrained kinetic danger. She peers at Sean, and Sean is exposed. She looks at Anna, and it’s only through her eyes that we recognize Anna’s desperation. She’s the film’s Cassandra. She knows everything, but no one wants the curtain to be pulled back, the spell to be lifted. Who wants to know everything? What good could that possibly do?

Until now, “Birth” has only been available as a subpar, overproduced DVD, and then in an inconsistent stream more tantalizing than satisfying. Leave it to Criterion to finally come through with a gorgeous 4K restoration supervised by Glazer. As per usual with this format, the uncompressed DTS-HD 5.1 surround Master Audio soundtrack is the real revelation, no matter how lovely the visual component of the presentation. New interviews with camera operator Craig Haagensen and Eric Swanek join archival b-roll press materials and an essay by Olivia Laing that rounds out this essential resurrection.

I teach “Birth” every year for my upper-division film students. To be able to show it now, as it was intended to be seen, is not only an extraordinary privilege but also, I think, an essential tool that demonstrates the possibilities of this medium to expand our understanding of ourselves and the universe we occupy. How art is still being made that is as ineffable and miraculous as great art has always been. It is a stunning tribute to one of the great films of the new millennium, back when it was young. We were all young. What a pleasure to spend this time again in the company of it reborn.

from Roger Ebert https://ift.tt/5tEjyCa

.png)

.png)