The remarkable year for film has already been captured in this feature of the ten best movies of the year, and this one with over 100 works cited on individual lists. It’s time to talk about performances! We asked our regular contributors to pick a performance this year they loved, and the results capture the diversity of genre, tone, and even acting styles in the art form.

There were some rules, including that each film could be represented by only one entry, which is one of several reasons this list is nowhere near comprehensive for ALL the great acting of 2025. There are performances by Emma Stone, Teyana Taylor, Benicio Del Toro, Wagner Moura, Timothee Chalamet, David Strathairn, and many more that we adored but aren’t included below. Consider this a snapshot of the great acting of 2025 more than the entire picture, but it’s a beautiful one, nonetheless.

Joel Edgerton, “Train Dreams”

These days, we are constantly bombarded with TikTok influencers and shiny, happy people in TV ads “living their best lives,” whatever that means—but in Clint Bentley’s meditative, early-20th-century period-piece poem “Train Dreams,” Joel Edgerton plays a man for whom that concept would be utterly foreign, and maybe even embarrassing. Edgerton’s work might seem minimalist at first, but we come to realize that we’re watching a formidable actor sculpting a fully realized, complex performance.

Edgerton’s Robert Grainier is orphaned as a child, knows happiness for a few brief years before tragedy strikes, and then spends most of his life simply trying to get by in a harsh land, largely isolated from the changing world and only occasionally making meaningful human connections. This is the best he can do with the life he’s been handed.

Aspiring actors looking to break into film would do well to study Edgerton’s performance. He creates an authentic, lived-in character and brings a rough-hewn physicality to the role—but there are no theatrics, no self-conscious mannerisms. This is an understated, restrained performance, yet we see a broad spectrum of emotion conveyed through Edgerton’s subtle facial expressions. He is playing the rarest of movie leads: an utterly ordinary man who is nevertheless a fascinated and sometimes overwhelmed observer of the world around him—and a quietly fascinating human being in a myriad of small but lasting ways. –Richard Roeper

Jennifer Lawrence, “Die My Love”

If there’s such a thing as dejection incarnate, Jennifer Lawrence has mastered it in her raw portrayal of Grace in “Die My Love.” Post-partum depression and psychosis are in the awareness of the social zeitgeist, though they are often misunderstood and cloaked in shame. But in the throes of depression, sometimes shame is hard to come by when one is overcome with profound indifference and even anger. Lawrence embodies this spectrum with expert primality, using the beast of motherhood as a centerpiece for exploring the animal of her new selfhood.

On the other side of birth, Grace feels born anew, though not fresh; something has turned. The runtime of “Die My Love” seems to find her exploring her body as a new frontier, trying to move through the rot and find her way back to clarity. At times, Lawrence straddles behaviors that echo both animality and infancy: routinely exploring her territory on hands and knees, licking windows, and going limp in exasperation. She is erratic at times, and carefully measured at others, unyieldingly sexual in bouts, and then hungry for isolation. Yet in all these dichotomies, whether lying prone on the floor of her wedding reception or tearing her nails to shreds on the bathroom wallpaper, Lawrence never tips off the head of the nail.

As far as dialogue goes, she’s usually silent or stripped bare, forcing her into a primarily physical performance that volleys between crawling, collapse, and impulse. It’s a ballet of true hysterics, chaptered by interludes of longing and frustration that Lawrence intermingles with deft hands. Grace is in the mouth of madness: sometimes in full, clawing-at-the-walls embrace, and other times, by means of a thousand-yard stare, desperate to find her way out.

Here, the same dryness that makes Lawrence so funny in comedic roles and interviews alike is weaponized into the perfect stoicism of Grace’s melancholy. But sadness takes many forms, and above all, Lawrence’s immersive performance feels like a curdled scream into the void: a moving, empathetic portrait of female ferality. –Peyton Robinson

Abou Sangare, “Souleymane’s Story”

Before the production of his immigrant drama film “Souleymane’s Story,” Boris Lojkine went through an extensive search for his leading actor. He did find the right one from Abou Sangare, a young Guinean immigrant mechanic who incidentally had no acting experience at all before. Because the titular character’s surname is also Sangare, we naturally wonder how much of Sangare’s life story overlaps with his character (he also came to France mainly for his mother’s welfare, just like his character, for example). All I can tell you is that he brings a lot of sincerity and honesty to his character, besides genuine authenticity.

As the camera steadily follows Souleymane through several eventful days, Sangare’s unadorned, non-professional performance effortlessly embodies his character’s ongoing struggle and conflict. This eventually culminates in the expected but undeniably powerful scene between Souleymane and a government official handling his application for political asylum. As Souleymane later becomes more honest about the long-standing pain and desperation behind his false life story to gain acceptance from the government official, Sangre is simply captivating, and we come to have a greater understanding and empathy for Souleyman instead of merely pitying him from a distance.

Not so surprisingly, Sangre received several notable awards, including the Breakthrough Performance award at the Gotham Independent Film Awards. I do not know whether we will see him more in other films in the future, but he does give one of the finest performances of this year. –Cho Seongyong

Jacob Elordi, “Frankenstein”

Those who judge acting often make the mistake of judging the writing instead of the performance. A great monologue, a witty exchange, a heartbreaking plot twist–these are the elements of acting, but brilliant screenwriting often deserves half the credit. Of course, this is not to say that a bad actor can’t mangle a screenplay, but it’s led to a dynamic in which it feels like we all take the physical half of performance for granted. Acting is more than speaking words. Acting is physical. The way a performer finds his light, hides his eyes, stiffens his spine, slumps his shoulders, etc., impacts an entire film as much as the lines he speaks. There was no more physically riveting performance this year than that of Jacob Elordi in Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein.”

From the minute Elordi’s Creature enters the frame, he’s using his giant frame to maximum impact. The way he stretches and moves his fingers, the way he first encounters the world, almost like a newborn child, and how that’s contrasted against the vicious killing machine later in the story. Elordi is constantly making choices about not just what this character is thinking and feeling, but how those emotions can be expressed through movement. It’s a performance that can be appreciated in silence, a reminder that great actors don’t steal scenes as much as they elevate a filmmaker’s vision through their physical choices. It’s arguably the best performance in Del Toro’s oeuvre, a perfect conjoining of an artist’s vision and an actor’s expanding skill set. –Brian Tallerico

Ethan Hawke, “Blue Moon”

“Nobody ever loved me that much.” This line becomes a tattered refrain for Lorenz Hart in Richard Linklater’s “Blue Moon.” A line uttered by Humphrey Bogart in “Casablanca,” the down-and-out lyricist gloms onto it as an explanation for his own self-destructive behavior. This internal narrative is at the heart of star Ethan Hawke‘s towering performance in the chamber dramedy, his ninth collaboration with Linklater. In Hawke’s nimble hands, Hart is a broken man with a front row seat to his own personal and professional demise. Diminutive in stature, but big in personality, Larry, as he’s known to his friends, has thrown himself into one last performance as Lorenz Hart, one half of Rodgers and Hart, the greatest American songwriting duo of all time.

Although Larry knows his days as somebody of note are waning, he can still play the part to a fault. It’s the after party for the premiere of “Oklahoma!,” the first of several hit shows Richard Rodgers (Andrew Scott) would go on to write with his new partner Oscar Hammerstein II (Simon Delaney). Still, Hart is determined to hold on to his old partnership, pitching new show concepts to Rodgers with the overzealousness of a used car salesman.

Hawke allows this desperation to seep in slowly, like a balloon letting out air over the course of a party. His passion and charm, at least at first, mask his self-loathing. He can banter with his bartender buddy Eddie (Bobby Cannavale) and share an intellectual discussion with fellow writer E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy) with the confidence of a bantam cock. But when it comes to matters of the heart, including his disastrous crush on the young and talented Elizabeth Weiland (Margaret Qualley) and his dissolving twenty-five-year relationship with Rodgers, the cracks begin to show. Hawke slowly folds his body into itself. His wide eyes become open wounds, where deflated passions leak out like pools of blood. Although Hart is a broken man, body and soul, Hawke plays this destruction all on the inside, projecting one last false sense of celebration into the night, as everyone who has ever meant anything to him heads out into their own futures, leaving him behind to wallow in his glorious past. –Marya E. Gates

Michael Cera, “The Phoenician Scheme”

By the time Michael Cera arrives in the quietly hilarious “The Phoenician Scheme” from director Wes Anderson, it’s hard to imagine any Anderson film going forward without him. Cera is so predisposed to the symmetrically off-kilter worlds Anderson creates. Despite this, he doesn’t simply default to tired, tried-and-true tropes. Instead, Cera comes alive in the minutia of his performance. There’s a constant, thrumming energy to his character that suggests he might float off if able to, with each physical flourish, be it how he holds himself or leaping across the frame, adding layers of specificity and charm. The script both works with what we know of Cera as a performer while allowing him to show off, from accent work to holding his own against heavyweights. In a rich ensemble of character actors and leading men, Cera eclipses them by reminding us of the magic in more minor gestures. From brushing off dust from a pretzel retrieved from his coat pockets to the sing-song delivery of his lines, the minimalist manner in which he approaches this character is in perfect harmony with the silliness and whimsy. So much so that, once the glasses and bow tie come off, and the coat collar is upturned, we, too, have been duped. –Ally Johnson

Amy Madigan, “Weapons”

Aunt Gladys, the surprise villain of Zach Cregger’s horror hit “Weapons,” is a clown. That’s scary enough to a lot of people in a post-”It” world. But the curly wig with the bizarre baby bangs, smeared ring of red lipstick, and heavy eye shadow and pancake makeup that actor Amy Madigan wears in character aren’t just an inspiration to drag queens and Halloween revelers — they’re armor. Aunt Gladys makes herself invisible by making herself hyper-visible, allowing those around her to dismiss her as an eccentric old bird who probably thinks that Jimmy Carter is still the president. But she isn’t as harmless as she looks. In fact, she isn’t harmless at all.

Madigan’s mannerisms change when Aunt Gladys goes barefaced; she no longer tilts her head to one side, and her wide, clueless smile is replaced with a tight-lipped scowl. This is when the character really gets serious. In these scenes, Madigan’s calm voice has a threatening undercurrent that speaks to the power concealed under her clownlike appearance. But that power is also a bluff. It conceals Gladys’ true vulnerability, which her young nephew, Alex (Cary Christopher), witnesses when he walks in on her alone in her bedroom.

As all good actors playing villains should be, Madigan is sympathetic towards Gladys, calling her “a very misunderstood woman” who’s “just doing what she has to do to get through.” Her performance plays on society’s simultaneous fear and dismissal of older women, embodying the desperation and bitterness that drive this storybook witch and her selfish, power-hungry ways. –Katie Rife

Leonardo DiCaprio, “One Battle After Another”

Among the greatest movie stars of our time, Leonardo DiCaprio has built one of those enviable careers that increasingly feels like a unicorn in cinema. He’s never been anything less than a stupendous actor, even as a young heartthrob of the ‘90s. And at 51 years of age today, his name still invokes the dream of Hollywood stardom. But to those looking closely, DiCaprio has been doing something else recently, in addition to reinforcing his uncompromising focus on cinematic excellence as an actor and producer. He’s been proudly embracing his age and leaning further into his disarming on-screen vulnerability, which has always been there behind his intensely sharp gaze, playing characters who are struggling to keep up with the rapidly changing world around them.

After playing the likes of an aging TV star, a murderous and morally conflicted war veteran, and a scientist with a case of midlife crisis, he is now a washed-up revolutionary in Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterwork, more in love with fatherhood than he’s ever been with changing the world. As Bob Ferguson, DiCaprio (hilariously donned in a weathered robe throughout much of the movie) is both sturdy and broken, both deeply relatable and maddening, both heartrending and laugh-out-loud funny. (DiCaprio’s exceptional physical comedy chops continue to be overlooked.) He is a single dad stuck in a rut in life, and he needs to step up at once to save the person he’s been living for, his daughter (Chase Infiniti), not realizing that perhaps he is the one who needs to be saved.

Because DiCaprio is always consistently excellent, the shades of humanity he brings out in Ferguson through a physically and emotionally agile performance might be taken for granted. But it shouldn’t be. To this critic, the road sequence in which Ferguson reunites with his daughter, holding that musical trust device, is the most heart-swelling scene of the year. In it and elsewhere, DiCaprio proves that he’s still that heartbreaker we fell in love with decades ago, but perhaps of a slightly different, more approachable kind. It’s a flawless turn from an actor who continues to give us a reason to go to the movies and experience stories and faces on the big screen. –Tomris Laffly

Naomi Ackie, “Mickey 17”

“Mickey 17” is, for the most part, unmemorable. After a slew of shifts for its release date and seemingly nonexistent marketing budget, it’s somewhat shocking anyone saw it at all. With her stellar support performance in Eva Victor’s “Sorry Baby,” Naomi Ackie is even more standout as the lead in Bong Joon Ho’s sci-fi adventure. While she showcased some of her depth in the 2024 thriller, “Blink Twice,” her role in “Mickey 17” allowed her to soak up the spotlight and be audaciously, unflinchingly gravitational.

When Nasha (Ackie) comes into the storyline, we, like Mickey (Robert Pattinson), are immediately smitten. Although her primary role is as Mickey’s love interest, her confident, playful demeanor makes it evident that she is much, much more. Nasha is no damsel-in-distress; she’s Mickey’s primary motivator. Ackie excellently matches Pattinson’s oddball energy, and she brings an enticing warmth to the screen that the story often lacked.

Her role is also much more complex than that of a lover; she’s a shipmate, a caring friend, and ultimately, the heroine. This layered identity is contained by a faraway spaceship with questionable leadership. Yet, Ackie acts with assurance that her character knows no bounds and will go great lengths for her found family. At times, it would be easy (i.e., lazy) to label Nasha as angry or aggressive. Ackie, without explicitly stating so, convinces us that every emotion explored and expressed is justified. Giving us, the audience, something gritty and authentic to admire, letting us know that Ackie is an actor to always look forward to seeing. –Cortlyn Kelly

Dylan O’Brien, “Twinless”

There’s an enchanting, rough-around-the-edges quality to Roman. His bro-type propensity to resolve conflict with violence is juxtaposed with a certain naivete that allows him to take others’ intentions at face value. You could call him a himbo, but in Dylan O’Brien’s career-best turn, this straight white dude who loves hockey transcends his brutish archetype for a more vulnerable depiction of heterosexual masculinity. Emotionally unequipped to grapple with the loss of his twin brother, O’Brien’s Roman clings to a bromance with the secret-holding Denis (James Sweeney), and it’s through this relationship founded on deceit (unbeknown to him) that Roman begins to process his grief.

Halfway through this dramedy, as the two characters sit in a hotel room, Roman pretends to be in front of his brother Rocky. Through this scenario, he wrestles with regret and resentment amid rageful tears. Layered with both profound sorrow and glimmers of genuine humor, O’Brien’s monologue viscerally captures the ambivalent, turbulent feelings Roman harbors about his sibling. The actor’s unrestrained crying while trying to formulate sentences resonates with such believable heartache that it almost prompts one to look away, as if to prevent getting caught up in the rawness of the emotion that O’Brien so potently evokes. On a path-redefining run as of late with roles in films like “Ponyboi,” O’Brien is twice as impressive here since he also puts on an opposing personality, that of a confident gay man, to play Rocky, the other twin. –Carlos Aguilar

Amanda Seyfried, “The Testament of Ann Lee”

“The Testament of Ann Lee” needs audiences to believe that Amanda Seyfried’s character could be the female embodiment of Christ. I’ll be the first to admit that I was a doubter of Amanda Seyfried. Despite showing her expertise in numerous projects, I always envisioned her as an actress who sings her best parts. Roles like Cosette in “Les Misérables” or Sophie in “Mamma Mia!” were how I always envisioned her. Broadly speaking, less dramatic roles. While her performance in Ann Lee still finds her singing, it’s more in line with her performances in films like “Jennifer’s Body” and “First Reformed”– physical performances that sneak up on you. The biggest difference this time is that she’s the one in the spotlight. No longer playing second fiddle to Megan Fox and Ethan Hawke.

As the founder of the religious movement that would become the Shakers, Seyfried’s Ann Lee dances and sings, her soul visible to all. There’s a sequence early in the movie that must’ve taken unbelievable courage to film. Seyfried follows those early haunting visions with enchanting choreography and a physical performance that demands almost everything from her. There’s a primal rage to the dancing that’s hard to describe without witnessing it. Undoubtedly, Seyfried benefits from Mona Fastvold’s direction, whose vivid imagination helped forge this powerhouse performance. Seyfried was gifted the role of a lifetime, and she absolutely delivers in one of the most demanding roles of her entire career. I’m no longer a doubter of Seyfried. –Max Covill

Rose Byrne, “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You”

One of the greatest tools in cinema is the close-up. Though this may sound obvious, it’s a part of the art form that allows us not just to look, but truly to see people in a way we rarely get to in our everyday lives. In 2025, there were few characters we saw more completely than Rose Byrne’s troubled mother Linda in Mary Bronstein’s illuminating “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You.”

From the opening moments where we get the first of many often extreme close-ups on Byrne’s frequently exhausted face to the quietly shattering finale when we see her for the first time through the eyes of her daughter, her performance is nothing short of astounding. Even as the film is less a reintroduction to the longtime performer than a reaffirmation of her immense talents, it’s this role that gives her the fullest canvas of emotions to explore. In nearly every frame, it falls to Byrne to carry the film’s unexpected moments of dark humor just as she does the heightened, heartbreaking portrait of motherhood. She does so with a force that is on par with the work of the late, great Gena Rowlands in the enduring “A Woman Under the Influence.”

While this is praise she already more than earns in every one of the film’s evocative escalations, Byrne also excavates emotions all her own. She’s a grounding force in a whirlwind of a movie, finding a gentle grace that knocks you flat. –Chase Hutchinson

Tessa Thompson, “Hedda”

When paired with Nia DaCosta, Tessa Thompson is at her absolute finest as a performer. If her performance in their initial collaboration, “Little Woods,” was an appetizer, “Hedda” is a buffet and more. In the queer reimagining of Henrik Ibsen’s play, Thompson’s performance as the titular Hedda Gabler is mesmerizing in every frame.

She may be the smallest person at her own party, but Gabler stands tall over everyone with her pure charisma and cunning behavior. Brash, classy, confident bisexual agent of chaos who weaponizes her femininity to dominate over everyone, whether it be her husband, George (Tom Bateman), or ex-lover Eileen (Nina Hoss), who she strongly yearns for, or her ex-lover’s new lover/writing partner, Thea (Imogen Poots). Thompson is the ringleader of destruction, and in traversing channels, the energy of a youthful, bratty child trying to get her way. In a way, Gabler is that, as the wealth she had to live comfortably as a child is gon,e given the loss of her war-coveted general dad’s passing.

Exuberantly, Thompson employs her entire skill set to elevate DaCosta’s portrait of a distraught woman attempting to preserve her remaining financial wealth and power as the consequences of her past impulsive actions resurface in real time. Of course, with the film subtly taking account of her race and sexuality within the 50s setting, there’s an overall sensation in witnessing an antagonistic Black bisexual lead cling to her power. Thompson’s showstopping portrayal of Hedda Gabler is a resounding testament to persistence, beyond the dissatisfaction of life and her efforts to maintain her freedom and fluidity, no matter how many fires she stirs along the way. –Rendy Jones

Ralph Fiennes, “28 Years Later”

“28 Years Later” wasn’t the sequel anybody expected to follow Danny Boyle’s zombie-horror parable. Still, this new film’s focus on one boy’s coming-of-age in post-apocalyptic Great Britain allowed it to succeed on stranger, more intimate, and surprisingly emotional terms. As young Spike (Alfie Williams) accompanies his mother (Jodie Comer) to the mainland to seek a cure for her severe illness, the pair encounters the enigmatic Dr. Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), who has lived in isolation since the Rage Virus outbreak. Once a general practitioner, Kelson is considered mad and was last seen collecting hundreds of dead bodies; shredded, stained orange-red, and quoting Shakespeare, he certainly cuts a peculiar figure. But it’s with the introduction of this medicine man, played with a miraculous mix of gumption and grace by Fiennes, that “28 Years Later” emerges as a daring meditation on the inevitability of death in our lives, the dignity we can find in facing mortality, and the meaning we must make in mourning others.

After Kelson leads Spike to a monument he’s built from human bones, the doctor explains that this is a form of memorial. He invokes the Latin concept memento mori: “Remember, you must die.” Yet as he consoles Spike, Kelson speaks another phrase, memento amoris: “Remember, you must love.” Only an actor of Fiennes’ gravitas could hold together a picture as thematically ambitious as “28 Years Later.” As Kelson yearns to restore compassion to a world that’s forgotten how to grieve, his performance gives the film a poignant, haunting poetry. –Isaac Feldberg

Wunmi Mosaku, “Sinners”

There’s a moment in “Sinners” when the joy curdles, blood is in the air, and survival isn’t bound to bravery but discernment. That wisdom, the ability to anchor the others within a storm of terror, is Wunmi Mosaku’s Annie. Her presence at the juke joint makes us believe: If survival is a lie, love will abide (even amid the call of evil).

If you’ve seen Mosaku ignite the screen in “Lovecraft Country,” or found yourself wishing she had more to do in “Loki,” you know her acting is planetary: it has gravitational pull. When she’s on screen, all eyes are on her. And it’s her earth goddess conjure woman who turns the old magics into a force field of protection.

That’s Mosaku’s magnetism. Annie isn’t a sidelined partner for Smoke, and she’s never a damsel, because she’s a parallel for Sammie. Both are ruled by faith and gifted with paranormal abilities, but where his blues calls the vampires, Annie’s Hoodoo is the only way to fight. He’s the beacon, she’s the barricade. Mosaku seamlessly channels the many sides of Annie—mourning mother, lover, guardian, and font of ancestral knowledge—through every gesture and assessing gaze: the way her hands linger over a mojo bag, the warning to leave Smoke behind and enter the afterlife as Elijah, the steadying resolve in her eyes, the way she catches every clue and questions every supernatural twist.

Annie is strength, not spectacle, and because she’s rooted in the fertile soil of the “Sinners” saga, Mosaku’s artistry blooms. –Sherin Nicole

Jessie Buckley, “Hamnet”

“I don’t know what Jessie Buckley is or where she came from,” says her co-star Paul Mescal in a promotional reel for “Hamnet,” “but she is God’s gift to this Earth.” Truer words have never been spoken. As William Shakespeare’s (Mescal) wife Agnes, Buckley achieves the kind of acting glory even the most gifted performers rarely achieve. Not only is Agnes different from the narrow-minded busybodies around her—she dozes at the base of a colossal tree; she shares a mystical bond with her falcon—she will use these differences to bend reality to her will (pun unintended). Her confident gait doubles as evidence of her ramrod spine, which remains upright even in the most harrowing moments of her life. Her romance with Will sparks a physical and emotional push-and-pull, creating sensational on-screen chemistry.

Watching Agnes calmly square off against her mother-in-law, Mary (Emily Watson), is a delight, as the former believes in a childhood full of wonder and play. At the same time, the latter knows only repressive misery. When loss comes to Agnes, Buckley shatters the screen. She is desperation incarnate, limbs akimbo, hair askew, as she flings herbs and salves to save Hamnet from the plague. When he is gone, the guttural roar she emits from the deepest, darkest part of her soul feels like the dissolution of the universe.

But we are altogether reborn when Agnes watches the first stage performance of “Hamlet.” She cycles through rage, indignation at her dead son’s name being spoken, but slowly, she realizes that by (literally) reaching out to art, she can give her son’s soul, and herself, peace. For all the devastation wrought over the course of 126 minutes, the film’s last few seconds are pure elation, as Buckley turns her face up and laughs, the sorrow and her body taking flight as Agnes finally returns to join the living. If Shakespeare summed up the human experience in his body of work, then Jessie Buckley has done the same as an actor. –Nandini Balial

Jai Courtney, “Dangerous Animals”

If you’re anything like me, you’ve been waiting for Jai Courtney to reach his final form. The handsome Aussie was positioned as an American action star until David Ayer asked him to be a scumbag Captain Boomerang, and it was like the bogan drongo inside him came alive. He’d been belted into Hollywood stardom, but the man needed to swim free. Sean Byrne gave him a dye job, a scar, a camcorder, and pushed him into the open waters, and he swam. Courtney clearly had to rebel a little against his star training to reach the point of unselfconsciousness, but few performers this year wore it as well as he did. He is as beautiful and as bad as any of the sharks to whom he feeds tourists. The perfect cheek muscles twist upward in a Mona Lisa Smile, and you know someone’s about to die.

Like John Jarratt in “Wolf Creek,” David Argue and Chris Haywood in “Razorback,” Eric Bana in “Chopper,” and Daniel Henshall in “Snowtown,” he’s created one of the best boogeymen in the nation’s cinema. Just hearing him chew the words in his real accent is like watching Hollywood melt in a crock pot. This is what cinema is. –Scout Tafoya

Théodore Pellerin, “Lurker”

Some performances creep up on you, slowly, even patiently. At first, there appears to be nothing remarkable, and then suddenly, they snap, crackle, and pop. Théodore Pellerin’s performance in director Alex Russell’s “Lurker” is one such example. At first, all we see is a socially awkward young man who is drawn into the orbit of an on-trend music star. What unfolds is the story about the power imbalance between two burgeoning friends and how one’s usefulness is the most valuable currency. From behind the uncomfortable construction of the film’s broader themes, Matthew slowly reveals a transformation that has gone unnoticed. Pellerin honors the relationship between his internal and external selves, and in one captivating scene, shows the vain transformation underway through his body language and telling sidelong glances. All of this is to observe that Pellerin empowers his performance, not allowing the plot to expose the character at chosen moments. Instead, the plot is driven by the character’s emotional and psychological rhythms.

As Matthew gradually reveals himself, we are forced to question how sympathetic and likable he is. This spirals outward to explore themes of learned patterns of behavior and frames the film as a moral play about losing oneself. Pellerin, however, invites deeper consideration of the character’s psychology and whether his experiences awakened something in him that had been lying dormant. Pellerin’s success is in crafting a layered character that doesn’t push the audience away, but ratchets up the discomfort as we sympathize with and struggle to reckon with a character that speaks to a part of us all. –Paul Risker

Frank Dillane, “Urchin”

Watching Frank Dillane’s character Mike take a shower in director Harris Dickinson’s “Urchin” told me all I needed to know about this spiraling drifter, who we’ll come to love and mourn. Mike approaches the hot water with recalcitrance and intrigue, as if he’s encountering a friend or lover with whom he’s fallen out of touch. When the droplets hit, we see relief flood his visage as he finally allows himself to exist without judgment or self-deprecation. From this sequence alone, thanks to Dillane’s performance, we’ll learn so much about who he is, the larger forces that are at work against him, and a bit more about the traumas keeping him shackled.

Dillane seems to intuitively understand how important these smaller, “in-between” moments are to understanding and embodying character, and “Urchin” is a film that’s filled with beats where the camera seemingly lingers on him for a second too long for comfort. Still, Dillane uses that to reveal a new multifaceted layer to Frank. Take a moment where, after he is given a new job as a cook, he practices saying “Yes, chef,” to himself. He repeats the phrase, chewing it over like a food he hasn’t tasted before, yet is instantly taken with.

But it’s in that moment where we learn more about his character. It’s a tricky balance: “Urchin” neither justifies Mike’s behavior nor critiques the ineffectiveness of assimilation as a tactic for true transformation. The structures and pace of life are antithetical to the kind of presence and slow, ruminative change needed to help those most in need, and we mourn for Mike for both what he can control and what he can’t. In Mike, we see the see-saw nature of the reality of deconstructing addiction; it’s never straightforward and always looks worse before it gets better. Dillane’s radiance and honesty ensure we pity or judge him as much as we condemn the systems that would rather benefit from his withdrawals than his sobriety. Dillane embodies Mike in a way that we never see the verisimilitude of performance. He teaches us how to breathe again, one attuned to Mike’s tortured, tender soul. –Zachary Lee

Indy the Dog, “Good Boy”

I have a niece who is a dog: her name is Evee, and she is the light of my life. I have a fear, its weight is gargantuan, and its roots are mangled and snarled around a deep-seated guilt: that I will hurt myself when I am watching Evee, and nobody will be able to help her. It’s a fear inspired by my actual fuck ups, and so I have promised myself that when I look after Evee, I will be good. In Ben Leonberg’s “Good Boy,” I see my worst fear grow to even more monstrous proportions and morph into Indy the Dog as he watches his owner, Todd, his best friend, grow sick under death’s clawing shadow.

Near the end of the film, Todd chains Indy, who has been diligently questing throughout the film to protect his best friend from the murky death only he sees creeping toward Todd, to a doghouse and leaves him with a bowl of kibble, so Indy might be easier to save. Indy is crestfallen but undeterred, he breaks free even as the monster seems to come for him, and runs up to Todd, but it’s too late. Todd has committed suicide. Watching this moment, I always weep, because I only ever thought about nobody finding Evee, not about her own sadness. I see it in Indy’s sweet little face, the way he quietly sits on Todd’s bed, guarding his dear friend, still.

That’s the thing about this movie, it’s not just about our feelings toward our dogs, it’s also about our dogs’ feelings, their hopes, fears, their love. In Indy’s deep, warm amber eyes, in his soft brow that furrows in understanding and widens in terror, in his tail that wags with joy at seeing Todd or falls still with apprehension and knowing—in Indy, we see how much we mean to our dogs. “Good Boy” doesn’t have a happy ending, and Indy, as he is driven away from the home where Todd dies, is more still than before; his best friend is gone, even if he himself is okay; grief is setting in. When we leave, our pets will be heartbroken.

I love this movie, even as it confirms and never quells my fears of leaving Evee, but I am also grateful to it, to Indy, for showing us what it looks like for our dogs to love us, to need us, to be scared for us. Indy’s performance of love, brave and bright in the face of fear, helps me to renew my promise tenfold; I will be good for Evee. –Alisha Mughal

Tom Blyth, “Plainclothes”

In Carmen Emmi’s “Plainclothes,” undercover cop Lucas (Tom Blyth) has been tasked with entrapping gay men at a local mall, a duty marred by the fact that he himself is a gay man. Throughout the film, which slowly unfolds into a romance between Lucas and Andrew (Russell Tovey), a man he meets on the job, Lucas’ growing paranoia manifests on Blyth’s face in darting glances, dilated pupils, and bodily ticks. As his relationship with Andrew progresses beyond casual sex, Lucas becomes desperate for affection, willing to put his job and life on the line for any semblance of closeness. His anxiety is showcased by the intercutting of grainy, VHS-style footage, the film’s shifting aspect ratios highlighting Blyth’s physicality and reflecting the suffocating constraints of Lucas’ double life.

A relative newcomer, the actor sheds all the grandeur of his previous leading role in “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes.” Instead of grand speeches, Blyth uses each passing expression on his face to convey Lucas’s anxiety, and the subsequent elation of finding someone he thinks he can love. Whether it is a look of disbelief passing over his face as Lucas and Andrew have sex in a minivan, or a feverish hopefulness as he asks to make their relationship official, the desperation of this character never wanes. Blyth’s raw vulnerability comes to a head in the film’s climactic finale, which explodes in a revelation filled with screams and gasps. It proves that Blyth’s future as a leading man is incredibly bright. –Kaiya Shunyata

Josh O’Connor, “Wake Up Dead Man”

Josh O’Connor’s Father Jud is a man in crisis. In the small-town parish that’s his own personal Gethsemane, he’s anguished, volatile, and guilt-ridden, tempers made all the worse by the fact that his heart is in exactly the right place; he has a shady, bloody past, and he’s still working on it. In a paradox that speaks to how the nobility of our intentions so seldom lives up to our words or actions, Father Jud simultaneously radiates authentic love and hope for the good of humankind, yearning to help those who share a similar darkness find the light. This church’s parishioners have gone astray, but he can’t save them before he saves himself.

It’s not since Andrew Garfield in “Silence” or Ethan Hawke in “First Reformed” that an actor has so profoundly captured spiritual struggle, embodying the inner battles of the soul we all experience. As if to demonstrate that conflict, multiple scenes in “Wake Up Dead Man” demand O’Connor’s performance to turn on a dime. Father Jud quickly pivots from sobs of despair into friendly debate against Benoit Blanc’s Hitchins-styled atheism, only to break down in tears once he “felt like a priest again.” Later, in the film’s best scene, annoyance at a frustrating phone call dissolves into rivers of empathy for a woman in need. It’s a deceptively tricky part that requires a whole range of ever-shifting feelings, playing the torment between our best and worst selves. It’s a magnetic, utterly compelling turn, with O’Connor as much a shepherd to the audience as Father Jud hopes to be for his flock. –Brendan Hodges

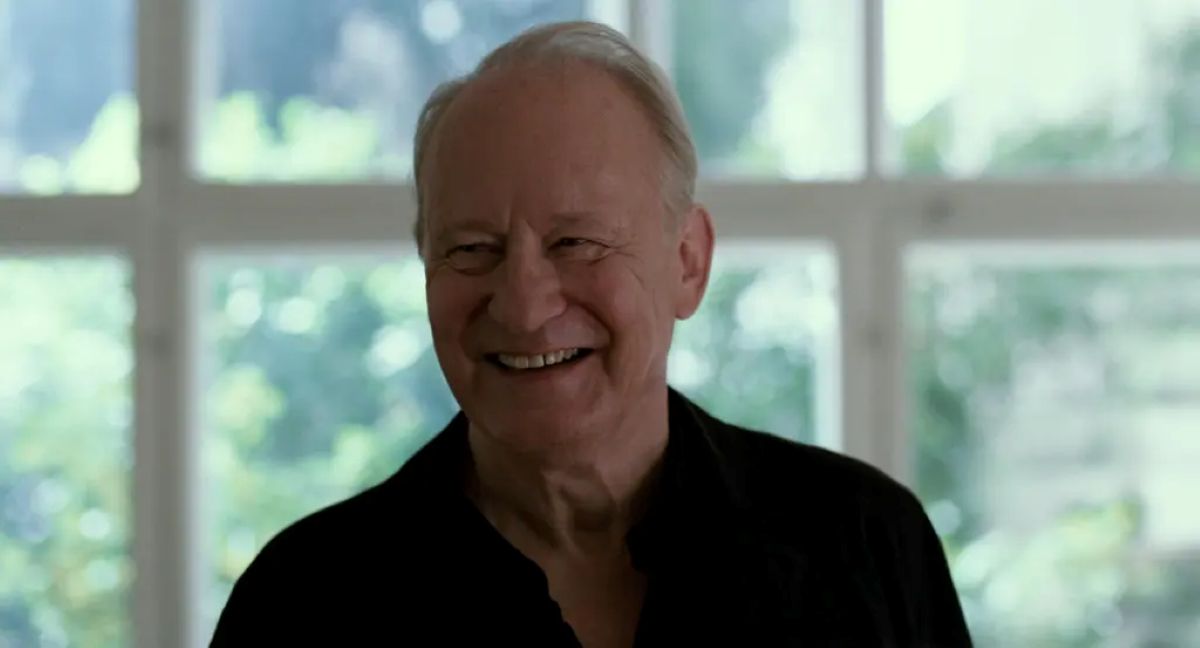

Stellan Skarsgard, “Sentimental Value”

There are myriad movies about making movies, and even more about fathers coming to terms with their children’s actions and reactions. Yet it takes a special film and an extraordinary performer to wring reality from what could easily be tired clichés, forcing viewers to confront their own prejudices and presuppositions and to focus instead on this particular paternal figure. Leave it to Stellan Skarsgård to make this magic trick seem so effortless, with emotions from the sardonic to the sentimental delivered with documentary-like verisimilitude.

In a year where on the small screen Skarsgård elevated a sci-fi streaming show to a status befitting its mythic standing in pop culture, his would be a talent worth championing on any end-of-year list. Yet it’s his deft, subtle, precise portrayal in Joachim Trier’s “Sentimental Value” that best mixes his trademark icy assuredness with deep yet reluctantly expressed emotionality, an exercise in bravura craftsmanship that would never dare to succumb to lazy showiness or maudlin meanderings. This patriarch of the film’s remarkable ensemble (with a handful of other performers equally comfortable on any best-actor list) is the heart of one of the outstanding accomplishments of this cinematic season.

Skarsgård’s often quiet performance is worthy of being championed as loudly as possible. Even though this title was arguably robbed of a rightful Palme d’Or following its Cannes debut, his exquisitely nuanced take, and the film as a whole, easily deserve to be considered one of the year’s absolute finest. –Jason Gorber

Margaret Qualley, “Honey Don’t!”

There have been several strong performances in films, but I have to say that one of my absolute favorites was in a movie that hardly anyone saw, and many of those who did clearly did not care for it at all. The film in question was “Honey Don’t!,” Ethan Coen and Tricia Cooke’s follow-up to their equally maligned “Drive-Away Dolls,” and the performance in question was the one delivered by Margaret Qualley, who was terrific in that earlier project and who is even better this time around. In this LGBTQ-themed riff on the detective movies of old, she plays Honey O’Donoghue, a private eye whose investigation into the mysterious death of someone who had just hired her for unknown reasons leads her to cross paths with a corrupt mega-church, a troubled runaway niece, and a cop (Aubrey Plaza) with whom she embarks on an unexpected and cheerfully horny relationship.

With her unapologetically brash and bold approach to matters both personal and professional, Honey is the kind of character that Barbara Stanwyck might have played once upon a time. Qualley perfectly captures her flip, offbeat manner throughout with a performance that is both whip-smart and hilarious, especially in her scenes with Plaza, no slouch in the scene-stealing department herself. Over the last few years, Qualley has become one of the most reliably entertaining new screen presences around, and her work here is as good, funny, and memorable as anything that she has done to date. Ignore the naysayers—the film is a blast from start to finish, and Qualley is even more so. –Peter Sobczynski

Vincent Cassel, “The Shrouds”

David Cronenberg made no secret of the fact that “The Shrouds” was a very personal movie, and having his leading man Vincent Cassel styled with a distinctively Cronenbergian haircut only drove that point home. His mournful tale of bereavement blending with conspiracy starred Cassel as Vincent Karsh, a businessman who invents a form of graveyard surveillance, allowing grief-stricken people such as himself 24/7 access to footage of their loved ones’ decomposing corpses. Cassel taps into both the overwhelming agony of being a full-time mourner and the gallows humor that death inevitably inspires. In maybe the most awkward first date in 2025 cinema, he acts like a proud parent when he shows off a video of his wife’s body via his phone.

He’s an actor who’s always succeeded in blending charm with a sinister edge, which makes his performance in “The Shrouds” so uncanny. Karsh is a sensual romantic who has cloaked himself in chilly professionalism to deal with his loss. Still, as he descends into paranoia over his technology may have been hijacked by nefarious forces, he becomes curiously passionate in his tin-hat scheming. It’s a very Cronenbergian character—Seth Brundle with more foresight but all the same delusions of grandeur—played by an actor acutely on that wavelength: Steely but manic, reserved but horny, grotesque yet intensely human. It’s amazing it took this long for Cassel to become a Cronenberg leading man, and not just because of the haircut. –Kayleigh Donaldson

from Roger Ebert https://ift.tt/UBIbPs8

.png)

.png)